PROVINCIA DE CHIMBORAZO

April 5 2025—3800m above sea levelWomen with white round hats and green wool skirts stand in a queue with their soup bowl. I watch from afar, admiring a scene out of an 1920s documentary movie.

We’re at 3800 meters, in a tiny village surrounded by green chakras—traditional farming systems used by Andean communities for generations, where they mix different crop species to adapt to climate change: corn (choclo), potatoes (papa), quinoa, and mashua, a sort of mushy sweet potato. If one crop is affected by pest or bad weather, the others survive, ensuring food availability year-round.

At lunch, I join a group of eight women, each meticulously weaving a piece of fabric, and almost all called Maria. Some speak Spanish, but most only speak Quechua. They’ve been living in this village since they were born, working the land for the past forty years. Most have never ventured further than the local market a few roads below. They shared pieces of their lives: their favourite foods, their hopes and fears for the future. They talked about their mothers, from whom they learned everything: how to care for Pachamama, how to read the clouds, how to save seeds, and how to pass that knowledge on.

A few spoke of the hail that recently destroyed some of their crops—something they said never happened when they were young. I sensed a melancholic blend of hope and fear in their words, unveiling a faint uncertainty about what’s to come.

They asked me what food we grow in Lebanon. I talked about olives and their beautiful trees, realising I didn’t know much about native food grown in my own country.

ATOCHA, PROVINCIA DE COTOPAXI

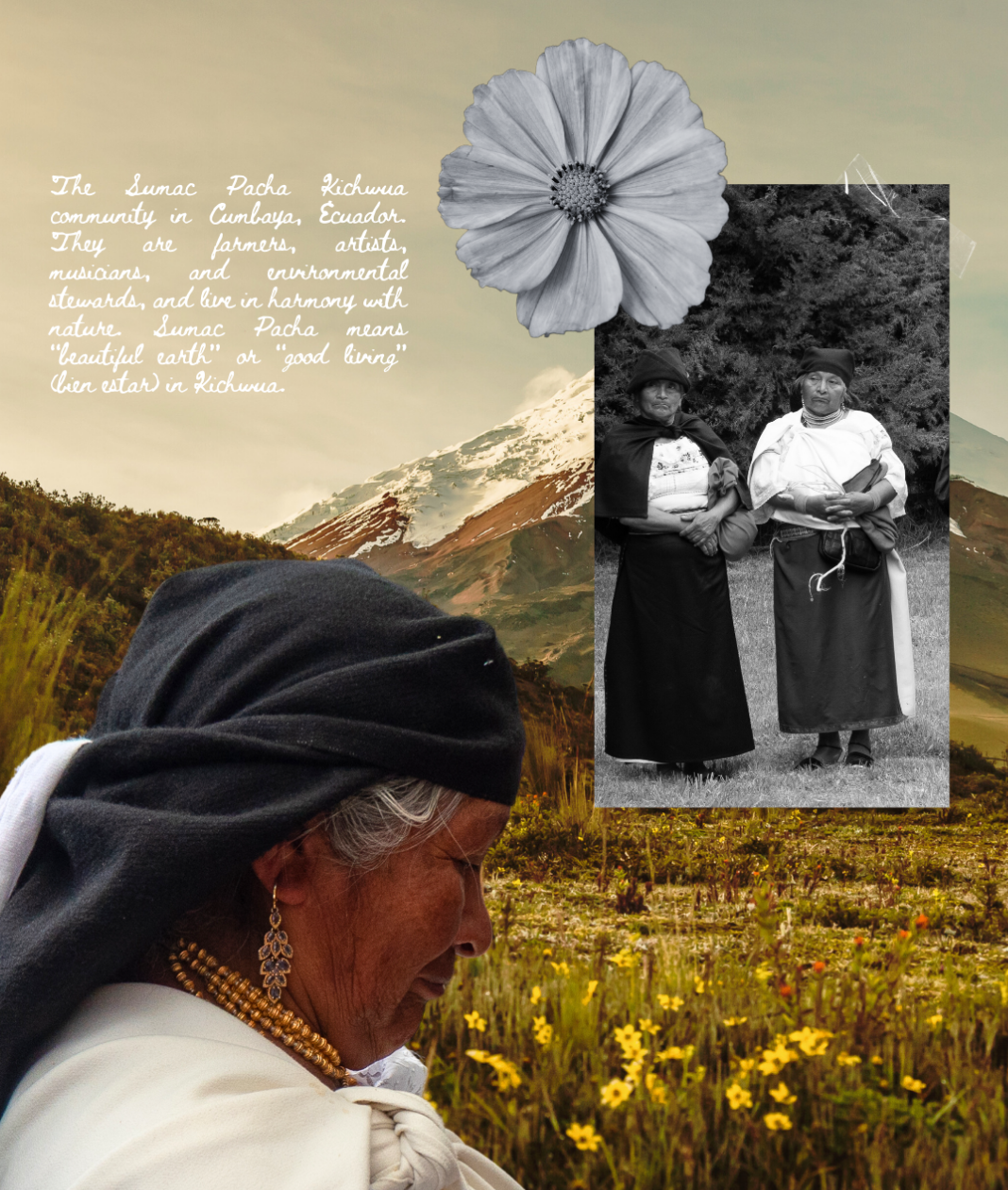

March 28, 2025—3400m above sea levelTheir hands show the reality of their daily life. Rugged, nails filled with dirt and dried blood, skin textured like sandpaper. As they stand proudly in their field, hands in pockets and feet in the mud, I admire Quechua women’s impeccable style. It’s in the little details: that feather, that ribbon of cobalt blue woven into a braid, that patterned scarf used as a belt, those alpaca socks, that golden earring. She smiles and her face lights up with a thousand wrinkles, carved by laughter, sun and time. Completely unbothered by modern beauty standards, she reminds me that joy on a face beats any Vogue cover.

Each community we visited had a different signature hat. In Quechua communities across Ecuador, traditional hats are symbols of identity, culture, and history. Each style reflects the wearer’s community roots, with distinct shapes and materials marking regional differences from the high Andes to the Amazon. These hats carry meaning passed down through generations, connecting people to their land, history, and collective memory.

AYAMPE, PROVINCIA DE MANABÍ

April 16 2025—at sea levelI had my doubts heading to the coast. My colleagues in Ecuador all warned me about the region: gangs, kidnappings, murders, homemade bombs. “One person dies each day from gangs in Guayaquil”. Ecuador is going through a grave insecurity crisis because of narco trafficking, with the coast boasting some of the highest murder rates in Latin America. So I did my research. Contacted some people who lived there—because things often look worse from the outside. “It’s safe in the surf towns,” they assured me. Still, during the taxi ride from Guayaquil, when we passed black pickups with tinted windows and no license plates, the cab driver said; “If you see one, either pass fast or take the next turn.”

Ayampe was a curious mix of Western “hippie” energy healers doing cacao ceremonies, seasonal digital nomads who live in a bamboo house six months a year, chill local surfers and American expats. You get to pick your crowd, but I hope Ayampe will remain shielded from the Bali epidemic (so called “entrepreneurs” wrapped in yoga pants flocking to pristine surf towns, settling when it arranges them, leaving when the rainy season hits, all while eroding local culture. It’s the soft version of Western colonialism and surf towns in the Global South are amongst the most prone to it). I’d love to buy a house and spend a few months per year here, but would hate to partake in this gentrification process. I wonder, is there a middle ground?

The first week, waves were brown and mushy with onshore wind. But surfing in a swimming suit after months of wearing 5mm wetsuits, hoodies, boots and gloves, even a mediocre wave in 28°C water feels like heaven. Then, a huge swell hit the coast with three-to-four-meters impenetrable walls crashing on concrete sand. Fortunately, other spots light up when the big swells hit, and they’re only a short bus or taxi ride away.

When the swell went down, I was blessed with the kind of waves I like. I surfed morning and night, burned like a lobster, and spent my last week in Ecuador bathing in pure delight.

Favourite spots in Ayampe

-The empanada place in front of the restaurant Mulata - try it with a bit of sugar on top

-The French bakery Ohlala for its coffee (best in town in my opinion)

-The Mali Thai restaurant for its savoury breakfast pancakes, good internet, and perfect working spot in front of the waves

-Down the beach on the left towards the cliff, there’s a little bamboo cabin that offers shade, where you can sleep/read all day on the sand

-The jewellery store in front of The Barn

-Ayampe Guest House’s hammocks in front of the beach

-The view and the outdoor kitchen at Vistamar

-The breakfast at La Buena Vida Hotel

-The surfboards at El Refugio, rented a gem there, thanks Camillo ツ

Heading to the coast in Ecuador? Hit me up for tips on transport, hotels, safe taxi contacts, surf spots, and more ツ